Planning a plant bed requires both information about plants and information about the space-to-be-planted. So concurrent with making a database of native plants, I also measured and mapped the bed.

Identifying Constraints

I mapped it both vertically and horizontally, but the horizontal (top down) map was the most useful for planning. The vertical/elevation map was helpful for height constraints, but I otherwise didn’t use it. I could have just measured the height of the windows and be done with it. Our windows are about six feet off the ground. I don’t like when plants block windows, so I wanted to be sure to select plants that wouldn’t.

With the map, I had an understanding of my available space. I wanted to keep a two-foot buffer between the house and plants. Ideally, I would have a back row(ish) of evergreen shrubs, a middle row(ish) of mid-height plants, and a front row(ish) of lower-growing ground covers and perennials.

Developing Options

With my native plant database, I began looking at plant options. My initial query was for all plants that had a minimum height of less than or equal to 6 feet, light conditions include deep shade, and hardiness zones include 8a.

I exported that dataset to a spreadsheet and continued working there. I filtered out any plants that were labeled as medium or high flammability since this bed is next to the house. I removed plants with cultural requirements inconsistent with this bed. Plants that belong in a coastal ecoregion or a marsh, for example. And I filtered out any plants who, even with a minimum height under 6 feet had maximum heights that indicated they would obviously get too tall.

Unfortunately, the space and native plant constraints just didn’t allow that backbone of evergreen shrubs. Everything that was too wide or too small for the back layer. Some evergreen and semi-evergreen ferns seems to be my best bet for year-round structure so I pivoted: I had the width for one taller plant in a particular spot, I could use ferns as the middle layer and they could provide the year-round backbone, and perennials would remain the front layer. I presented these options to my wife:

- Tall back layer

- Euonymous americanus, “Hearts a'busting”

- Impatiens capensis, “Jewelweed”

- Middle layer

- Dryopteris intermedia, “Intermediate wood fern”

- Dryopteris marginalis, “Marginal wood fern”

- Polystichum acrostichoides, “Christmas fern”

- Ground layer

- Mertensia virginica, “Bluebells”

- Tephrosia virginiana, “Devil’s shoestring”

- Panax quinquefolius, “American ginseng”

- Phlox divaricata, “Woodland phlox”

- Trillium simile, “Jeweled wakerobin”

- Trillium vaseyi, “Sweet trillium”

- Trillium catesbaei, “Bashful wakerobin”

- Trillium luteum, “Yellow trillium”

- Stylophorum diphyllum, “Celandine poppy”

- Trillium cuneatum, “Sweet Betsy”

- Hydrastis candensis, “Golden seal”

- Sanguinaria candensis, “Bloodroot”

- Chimaphila maculata, “Pipsissewa”

- Galax urceolata, “Beetlewood”

- Tiarella cordifolia, “Heart-leaved foamflower”

- Trillium pusillum, “Dwarf wakerobin”

- Viola hastata, “Halberd-leaf violet”

- Anemonella thalictroides, “Rue-anemone”

- Anemonoides quinquefolia, “Wood anemone”

- Erythronium umbilicatum, “Dimpled trout lily”

- Chrysogonum virginianum, “Green and gold”

- Sedum ternatum, “Stonecrop”

- Tephrosia virginiana, “Devil’s shoestring”

She liked the shrub over the jewelweed. She generally doesn’t care for ferns, but is fine if that’s the only option. And she didn’t want to look at all the perennials to offer any preferences.

Checking Availability

It’s all well and good to have plant options, but what can I actually obtain? With my list of plant options, I used the Georgia Native Plant Society website to find native plant nurseries near me. Many of the nurseries list their inventory online, so I cross-referenced my list with the available inventories.

This process ruled out several options as they just didn’t seem to be available. I focused in on plants that seemed to be more widely available. I was tempted to plant a few of many different perennials, but was concerned about the bed looking unruly. I constrained myself to three different perennials, planted en masse, to ensure the bed looked intentional instead of weedy.

My selections, given Megan’s preferences and plant availability, were

- Euonymous americanus, “Hearts a'busting”

- Polystichum acrostichoides, “Christmas fern”

- Phlox divaricata, “Woodland phlox”

- Tiarella cordifolia, “Heart-leaved foamflower”

- Chrysogonum virginianum, “Green and gold”

Drawing It In

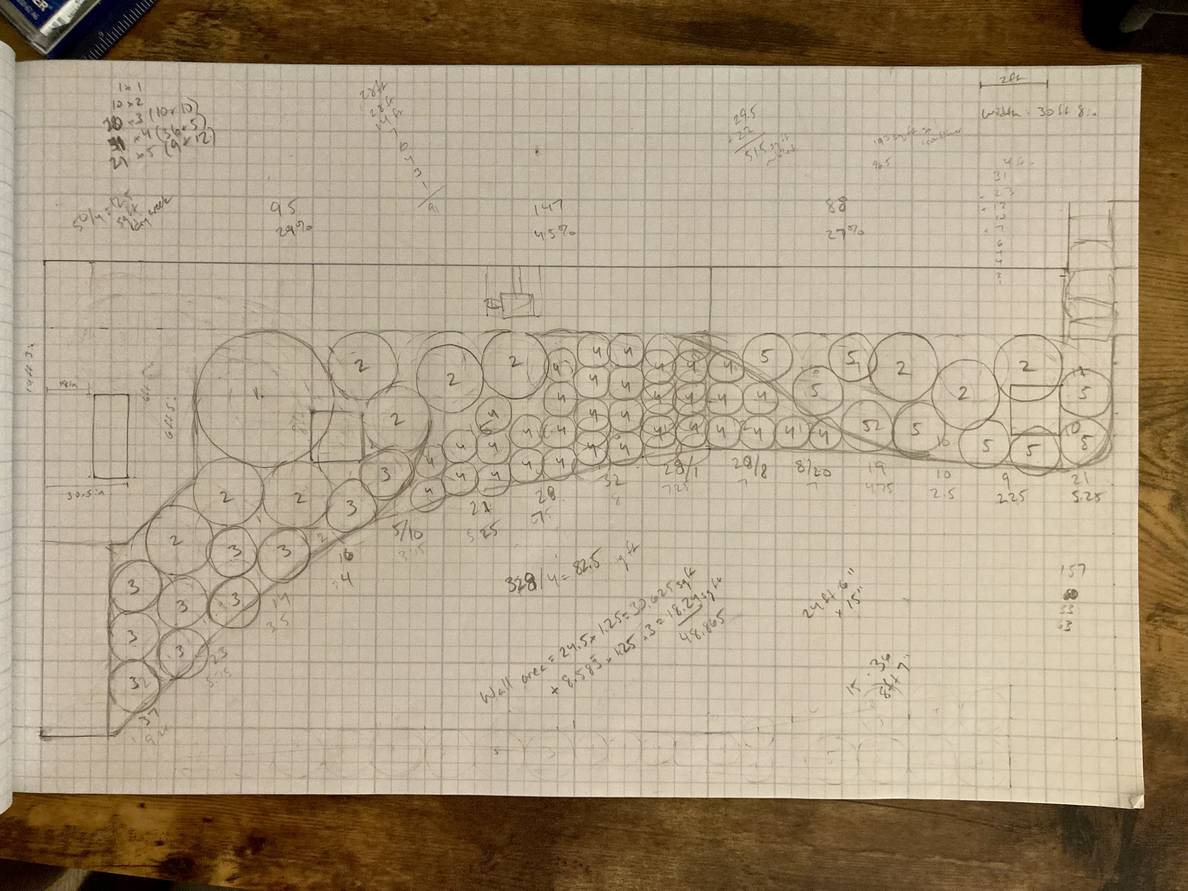

With the euonymous being the largest, I placed it on my map first. Then I drew circles for the ferns to give the bed structure and hide the legs of the deciduous shrub. Since Megan doesn’t like ferns, I did the minimum needed for the job.

That gave the remaining space for perennials. This bed is along a pathway, and on the other side of the path is a 15 inch wide planting strip before a retaining wall. I decided to mirror the perennials in the strip, but not strictly symmetrically. I would allot each perennial equal coverage area, but unequal between the main bed and the strip.

My initial approach was to calculate the perennial area, divide that by three (for each species), and then divide each area third by the estimate spread of its perennial. That gave me ~130 sq ft of area and around 100 (!!) plants!

Given the cost of plants, I decided it was worth my time to draw the circles on my plan to see how many could actually fit. I defined the three areas for the main bed and drew them in. I then calculated the area covered by each species on the main bed and balanced that area with the planting strip. So the phlox covers more of the main bed, but less of the planting strip, for example. This approach gave me 79 plants, saving me hundreds of dollars in plant costs.

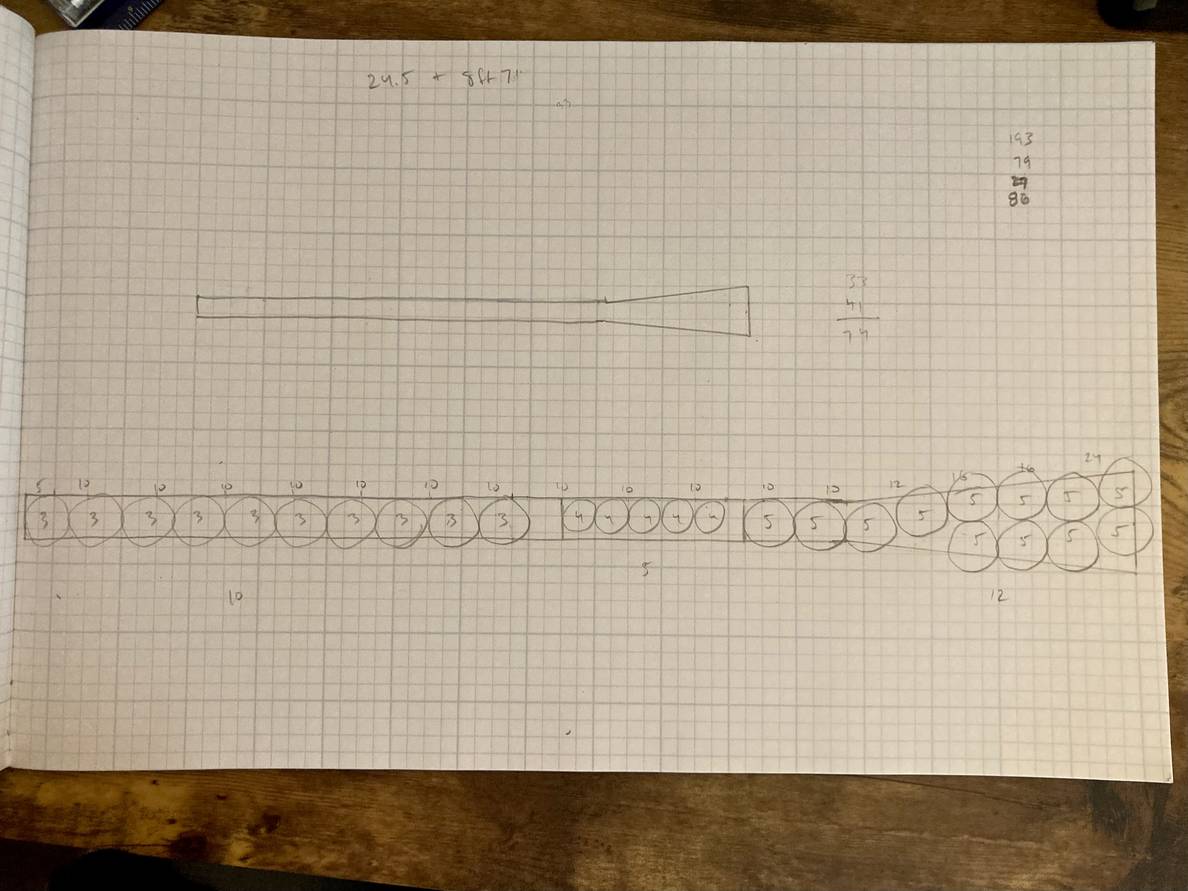

My final drawings looked like this:

(I didn’t bother mapping out the curve of the planting strip. I measured the center length, and then took measurements of the widening at the end, and drew it as a straight line.)

Epilogue: Kentucky Changes You

With the plan finished, we went to Kentucky for spring break, and I intended to begin acquiring plants once we got back. On our hikes in Mammoth Cave National Park, we saw many of the plants I had considered, including the phlox, the foamflower, and the Christmas fern! I was unimpressed by the evergreen Christmas fern: its fronds were flat to the ground. That’s not the evergreen structure I was hoping for. I found the reason on Wikipedia:

In winter, the fertile fronds die; the sterile fronds remain through the winter, and are often flattened to the ground by low temperatures and snow cover.

So change of plans: dryopteris marginalis instead of the polystichum acrostichoides! Fortunately they’re about the same mature size, with the dryopteris a touch larger, so I didn’t redraw my entire plan.